The Sacred Equation

Translated from talks given in Thai by

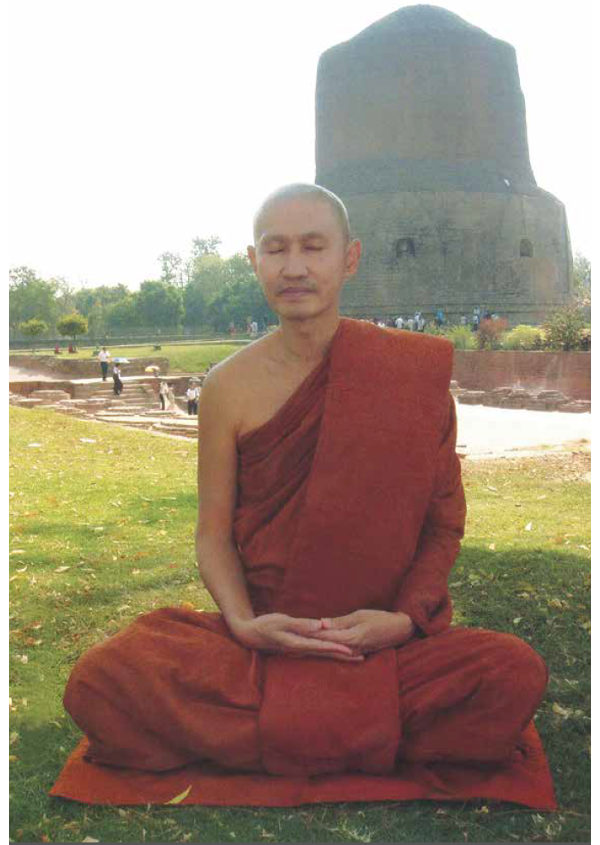

Ajahn Dtun (Thiracitto)

Translated from talks given in Thai by

Ajahn Dtun (Thiracitto)

At the heart of the Buddha’s teaching is the Noble Eightfold Path, which is divided into the threefold training of sīla, samādhi and paññā, moral virtue, concentration and wisdom. The combination of all three path factors is commonly known as the Middle Way, and it is this very combination which forms a sacred equation that ultimately results in peace, freedom from suffering, liberation and Nibbāna. The three factors are mutually supportive of each other: moral virtue is a foundation for concentration, concentration the foundation for wisdom, and wisdom is the tool that works for one’s deliverance. Removing any one factor from this sacred equation will prevent one from reaching the path that leads to true happiness, Nibbāna.

The main part of this teaching begins with a very simple question which Ajahn Dtun asked a group of laypeople whom he knew to be students of a teacher who emphasizes the practice of ‘watching the mind’. This practice focuses on watching the arising and ceasing of all the objects of the mind’s awareness, with the view that this is the most effective way to give rise to wisdom and thereby cleanse the mind of the mental defilements. Those practising this particular method tend to overlook or underrate the role that concentration plays in the development of wisdom.

Over the last 15 years this practice of watching the mind, while by no means new or modern, has attracted a great deal of interest and become very popular in Thailand. However, this new-found popularity has created concern among the more traditional forest masters, who stress that believing that the practice of just watching the mind can free it from the mental defilements is a great mistake. On many occasions over many years, the translator has listened to Ajahn Dtun as he patiently gives advice to steer these practitioners back to the correct path of practice of moral virtue, concentration and wisdom, the Middle Way as taught by the Buddha. He also explains to practitioners that in no way whatsoever can concentration be taken out of the equation.

It is hoped that by reading this teaching the reader will gain a clear view of the complete path of meditation practice, and understand that solely contemplating the mind is not sufficient to free it from the mental defilements. The assumption that the mental defilements arise within the mind, and so must be dealt with solely by contemplating the mind, is true but not altogether correct. It is true that mental defilements do arise within the mind and so must be let go of within the mind, but it is not correct to believe that one can start the work of cleansing the mind at this point. This practice, as Ajahn Dtun clearly shows, is for those already highly advanced on the path to liberation, as they push forward to reach the final stage of enlightenment.

Finally, I would like to acknowledge my debt of gratitude to all who have helped in bringing this book to fruition. For any errors that may still remain in either text or translation, the translator accepts full responsibility and humbly begs both Ajahn Dtun’s and the reader’s forgiveness.

The translator

Wat Boonyawad

2557 (September 2014)

Ajahn Dtun: Do you practise sitting in meditation at home?

Layperson: Not really, I’m a bit slack.

Ajahn Dtun: You have to reflect on death because it arouses the mind, warning it to not be heedless. Death is something we must frequently recollect, for if we don’t we will just go about occupying ourselves happily throughout our days and nights, letting time drift by as days turn into weeks, weeks into months and months into years, allowing our thoughts to proliferate about ‘at the end of the year…’ or ‘at the start of next year…’ without ever giving any consideration at all to death. Contemplating death brings our awareness back to the present moment. We will realize that the future is uncertain, so there is no need to be too worried or concerned about it. If we need to make plans of any kind, that’s fine. But once any plans for the future have been made, we return to establishing our mindfulness in the present, because it is right here in the present moment that the causes which determine our future originate. Hence we have to live skilfully in the present moment..

We mostly like to think about the future and forget to reflect that our lives are uncertain. This being so, we become careless and unconcerned, allowing our days to pass by in vain. And it is this laxness that causes us not to put effort into the practice of sitting meditation. Each of us should try asking ourselves: ‘Have I developed wholesome, virtuous qualities to the utmost of my ability throughout my entire life or not?’ or ‘If I were to die right now, would my heart1 be prepared for this?’ or ‘Does my heart possess sufficient merit to be born into a heavenly realm or not?’ or ‘Have I developed the spiritual perfections2 (pāramī) sufficiently or not?’ If we realize this isn't yet so, we should take up the practice of contemplating on death so as not to be heedless. We should frequently think to ourselves: ‘I could die any time soon’.

If we remain too contented with ourselves by failing to develop goodness and observe correct moral behaviour (sīla), and neglect to cultivate our minds through practising meditation, then should we meet with a fatal accident or develop a terminal illness, we won’t have developed any real goodness or virtue in our lives. However, reflecting on death gives us a prod and reminds us to go about the present as well as we possibly can. We will therefore search for ways to cultivate any good that we are able to perform.

When we live by a correct moral code of behaviour, that serves as the basis for the goodness and virtue that make us good, decent human beings. The moral standard that is appropriate or befitting for humans is to observe the five moral precepts.3 Observing these precepts makes one a good human being. When maintaining the moral precepts has become normal, our hearts will experience a degree of coolness and peacefulness because they are free from the distress and remorse that come from improper or immoral behaviour.

The moral precepts aid us in restraining our actions and speech. They work to control the mind so that we do not speak or behave improperly. For example, if greed or desire arise in our mind we can restrain ourselves so as not to break any of the precepts. Similarly, if anger arises we won’t physically harm another person. All our actions and speech will remain within the bounds of the moral precepts. We will be content with what we have. This means that if desire arises we won't compete ruthlessly with others or resort to violence and killing in order to obtain the objects we desire, but instead only go about seeking wealth or goods according to our intelligence and ability. Similarly, if anger arises we won't physically attack or kill someone, as we are observing the moral precepts. They therefore protect and control us by subduing our actions and speech.

However, even though we are keeping the five precepts, if we look closely at ourselves we will see that our mind is not yet calm. It is still restless and unfocused, actively thinking about all kinds of things: things to do with the past, things to do with the future. Sometimes the mind will think about unwholesome things, and at times it will even think about things that we don’t want it to think about. This is all due to the restlessness of the mind. If we are perceptive enough, a small insight may dawn on us: ‘Why is it that I can’t take control of this mind?’ When our hearts wish for happiness, why is it that we still experience unhappiness or feelings of anxiety, agitation and a lack of peace? We will see that the moral precepts can’t stop unhappiness and suffering from arising in our hearts. They only serve to control our bodily actions by preventing us from:

Hence moral behaviour calms our bodily actions. As for our speech, it is calmed by refraining from speaking any falsehood that would be to the detriment of others.

So by observing moral precepts we are able to control our actions and speech. Our mind, however, is still not peaceful. It remains worked up and restless, always beguiled by or lost in its thoughts and emotions. So once we’ve realized that our mind is agitated, we have to find a way to make it peaceful. But what must we do to restrain the mind, to prevent it from thinking all the meaningless things it wants, and from thinking unduly about the past or future? How do we stop all its restlessness, distress and uneasiness? To have the mindfulness and wisdom to govern the heart and to filter out all the bad, unwholesome things within it, including all our unhappiness and discontent, it is necessary for us to practise meditation so as to develop concentration. It is the practice of meditation that enables us to take control of our hearts.

Concentration is developed by bringing mindfulness to focus on a meditation object that is suited to one’s temperament, such as being mindful of the in and out breath or internally{ reciting the meditation word ‘Buddho’. When we have free time we should cultivate mindfulness and develop concentration in either of the formal postures of sitting or walking, practising for as long as time permits. Try to practise frequently. Work at it, really develop it. When it’s time to break from sitting or walking meditation, we must always try to sustain our mindfulness by being attentive to the mind’s thoughts and emotions. The common expression used for this is 'to watch the mind' (in Thai: Do jit). However, it isn’t really the mind that is being watched, but rather the contents of the mind, its thoughts and emotions. This is why you must have mindfulness by watching the thoughts and emotions within your mind: they are not the mind, they are just its contents, or mere states of mind.

All our thinking, whether it be about good things or bad things, or thoughts which generate greed, anger and suffering, is all just states of mind arising due to the mental defilements. They are not the actual mind itself. It is said: ‘Watch the mind’, but really it is the emotions or all the mental activity that are being watched. We go about identifying with our thoughts and emotions, believing them to be the mind. Whether it’s emotions of greed, anger or suffering, we say they are ‘us’ or our mind, but they are not. What happens is that we let our minds blend in with these emotions, and then we go calling the emotions ‘our mind'. That’s why I'm telling you to mindfully watch the thoughts and emotions within your heart.

With frequent meditation practice our mindfulness will become firmly established, and it can be put to use by ‘watching the mind’ or, more correctly, watching the mental and emotional activity within the mind. We will see what the objects of the mind’s awareness are and the effect they have on the mind. Whenever the eyes see forms, the ears hear sounds, the nose smells odours, the tongue tastes flavours or the body feels sensations of heat, cold, softness or hardness, the mind will be affected and will give rise to feelings of liking or disliking, happiness or unhappiness. We therefore use mindfulness to keep a watch on our sensory impressions and their resulting emotions. The mental strength acquired from practising concentration supports and firmly anchors one’s mindfulness. This in turn enables us to witness all the mind’s movements and feelings.

If we don’t develop concentration our mindfulness will be adrift, allowing the mind to be easily moved by its sensory impressions, moods and emotions. This state can be compared to a tall clump of grass. From whatever direction the wind blows, north, south, east or west, the grass bends and sways along with the wind. Our minds are no different from the grass, blown about by all the arising sensory impressions, emotions and thoughts. We need our minds to be strong, rock-solid, like a huge, towering mountain that remains unaffected by any storm. Send in any storm, even a violent tornado, and such a mountain remains unmoved by the wind and rain. The hearts of anāgāmīs and arahants4 are rock-solid, just like a mountain. If we are to make our minds firm and strong like theirs, we too must develop concentration. Through the practice of concentration the mind becomes peaceful, causing the body and the mind to feel light. Rapture, happiness and equanimity also then arise. At that time the mind will be perfectly still because it has been absorbed into its meditation object, becoming one with it or one-pointed. Outside formal meditation practice our mindfulness will be firmly established in the present moment, owing to the strength gained from developing concentration.

When sensory contact occurs it gives rise to a feeling of either pleasure or displeasure. Our faculties of mindfulness and wisdom will then examine this feeling with the aim of seeing its impermanence and thereby letting it go. The mind will remain unaffected because it can see that the thoughts and emotions are separate from itself; the mind is one thing, its thoughts and emotions another. They are seen as separate because of the mental strength and clarity which come to a mind that has developed concentration. This strength establishes the mind in the present and enables our wisdom faculty to assist by screening all our thoughts and emotions. We then see suffering or discontent whenever they arise, and search for their cause and a way to bring them to an end.

If we are not truly mindful we will be just like everybody else and unaware of the dukkha5 in our lives. On the whole our minds rarely see or comprehend dukkha. They much prefer just to think and be occupied and unaware, though we like to say we are mindful. So whenever greed arises it will know no limit, and when we are angry or have feelings of ill-will and vengefulness, our hearts will enter into these emotions, believing them to be ourselves. Nevertheless, we say we are being mindful. Thieves are mindful too. They lie in wait, ready to prey on some unwitting victim, watching this or that house to see if anyone is at home. Mindfully the thief watches, waiting for somebody to put something down or for the owner of an object to be off-guard. However, this is the wrong kind of mindfulness because it is based on wrong view.6

So what we have to do is use our sati-paññā (mindfulness and wisdom) to cultivate right mindfulness and right view or understanding. We also have to train our minds and make them peaceful through practising concentration. Once our mind has been made peaceful, it will cause both mindfulness and wisdom to arise. Sati-paññā will take care of and safeguard our hearts by filtering out the emotions of greed, anger and suffering. Sati-paññā will also clearly see any dukkha that has arisen and seek out its cause, and will search for a means to weaken these negative emotions or cause them to cease. However, if mindfulness is lacking we will be left totally at the mercy of the kilesas, the mental defilements of greed, anger and delusion. It is due to our not developing concentration that the mind wanders away, lost in its own thoughts, with its awareness ever drifting. If the mind has no brake, when one train of thought stops another immediately starts up; it’s never-ending. This is why we have to establish mindfulness here in the present moment. When we do so and the mind starts to think, our mindfulness and wisdom will be hot on its tail. As soon as one train of thought has come to an end the mind will begin with another, but it is at that precise moment that we introduce the meditation word ‘Buddho’ or bring our attention to focus on the breath. In doing so we interrupt those trains of thought, causing them to come to an end all by themselves. By continually re-establishing mindfulness in the present moment, our minds will begin to develop and improve. We have to build up sati-paññā in order to be in control of the mind.

And to what extent must we be in control? To the extent that we will only think about good, wholesome things, without thinking any bad or unwholesome thoughts. To have this amount of control over the mind requires us to develop concentration to an equivalent degree. What should we do when bad thoughts arise? We must use our mindfulness and wisdom to single them out and let them go, discarding them by not holding onto them. Those bad thoughts are not the mind. We don’t have to keep holding onto them. When we have bad thoughts, we don't have to speak or act on them. When such thoughts begin to arise in the mind we must use our sati-paññā to examine them closely. Sati-paññā will further consider the thought or emotion by asking: ‘Is this a good thought?’ or ‘Should I speak feeling the way I do?’ If we see the mood or thought isn’t good, we shouldn’t speak. Instead we just let it cease within the mind. We must rush to put out the fire, for if we don’t it will spread in an instant, to be expressed in our actions and speech, creating harm along the way. Just have a look for yourselves.

When we lack mindfulness and entertain bad thoughts which we express in our speech, we will think: ‘Oh, I shouldn’t really have said that. This is our conscience talking to us. In our heart of hearts we all wish for happiness and goodness. ‘I shouldn’t really have said that’, because we will see that having done so creates harm and gives rise to misunderstandings and arguments. It all happens because the mind doesn’t first screen its thoughts and emotions. This is why we have to develop concentration, so that we can have the mindfulness and wisdom to screen our thoughts and thus know whether we should express them or not. We have to be aware of the mind when it begins to move with feelings of anger or displeasure. The mind will want us to express those feelings, so we must restrain ourselves, enduring the impulse with mindfulness, concentration and patience. Use your sati-paññā to examine your thoughts. Think to yourself beforehand that this thought will be dismissed if it proves inappropriate to express it.

What should we do when we are feeling angry or displeased? We should cultivate mettā (kind-heartedness, goodwill) and forgiveness for others. Why are we angry anyway? Think about it first. We are angry because they did this or did that. Even so, why do we have to be angry? Can we not forgive them? We must look for ways to teach our heart to keep laying the anger down. Mindfulness and wisdom can resolve every problem, but they first have to be developed.

Ordinary human intelligence is completely incapable of abandoning the mental defilements. People can study as much and as long as they wish, graduating with a Masters degree, a Doctorate or even several degrees, but if they don’t keep the five moral precepts and thus lack a foundation in virtue and integrity, they will be at a total loss. Their intelligence will be nothing more than the intelligence of the kilesas, and those mental defilements are capable of corrupting everything. Regardless of how much they study, whether it be for a Masters or a Ph.D, or even if they have a high rank or position, if they have no moral principles their intelligence will easily find ways to make them behave dishonestly or corruptly. On the other hand, if we hold to moral principles the mind will think in an altogether different way. When feelings of greed arise and we desire to obtain something, we will think: ‘I don’t want that, I’m content with what I already have’.

In those who lack moral standards the mental defilements will be given a clear opening to function freely. If they occupy an important position, their mindfulness and intelligence may well lead them into dishonest or criminal dealings. This is their intelligence at work. It is not sati-paññā, mindfulness and wisdom. If those important people were insulted by someone, they might feel that their position gave them the power to order a gunman to do away with that person, because they don’t know how to control their anger and displeasure. We must therefore first curb our anger by way of moral restraint, observing the moral precepts, so that regardless of how angry we become we won’t kill or harm another person. So what should you do when you become angry? Be patient and endure it. Use your mindfulness and wisdom to reflect on why you are angry. Look for its cause and a way to let it go. There is a way out; there is a solution to everything. However, we have to start with a foundation of moral standards in our lives. Moral conduct is absolutely essential, but it is mostly overlooked.

We should consider having taken birth as humans most dignifying, since we generally regard humans as highly cultivated and superior beings. However, most people’s minds are not yet truly human. There are billions of people living in the world and a great many, despite their human bodies, do not possess minds that make them worthy of being called human. Instead they behave more like fiends from hell. They go about their lives robbing, mugging, harming and killing each other. Some will go as far as to be violent towards their parents, and some are even prepared to harm an arahant or the Lord Buddha himself. This is more like the behaviour of demons,7 ghosts, animals or some kind of being from hell; with all the ruthless competing, violence and killing in their lives, they’re not human at all!

If our minds are to possess the qualities that make us fully human, we must observe the five precepts. These precepts civilize humans by making our hearts good and wholesome. However, if we want to possess the mind state of a devatā (celestial being), not only must we maintain the five precepts, but we will also need to cultivate a sense of moral conscience and a wholesome fear of the consequences of bad actions. We must also regularly practise generosity. For those who wish to develop their minds further so that they possess the qualities of a Brahma god,8 it is necessary to cultivate both concentration and the four Brahma Vihāras, the sublime states of abiding. These four states are kind-heartedness and goodwill (mettā), compassion (karunā), sympathetic joy (muditā), and equanimity (upekkhā). When we develop these qualities we will have goodwill and friendliness towards our fellow humans and all other sentient beings. Within our hearts there will be a feeling of compassion and the aspiration to find ways to be truly helpful to others. We will also delight with other people when they experience success and happiness in their lives. And if it happens that we are unable to offer any real assistance to other people who are in need, we will let our hearts rest equanimously. Even we ourselves may feel distressed and uneasy, in which case we also have to learn to bring our mind to an equanimous state.

The Brahma Vihāras nurture our hearts by giving rise to peacefulness and coolness. They function as an antidote for the mental defilements, their purpose being none other than to counteract the kilesas. If our heart is full of defilements we will tend to be selfish and inconsiderate, thinking only of our own benefit. But if we cultivate mettā towards others we will have an antidote for any feelings of anger and ill-will we may have, thus making our hearts cool and peaceful, and less inclined to feel angry. When we have feelings of compassion and kindness in our hearts we will wish to help each other, assisting our families and friends according to our ability and means. However, if we are unable to be of any help, we must remain equanimous. By doing so we will be learning how to protect and take care of our hearts. There are some people who know no limits when it comes to wanting to help others. Whenever they know of somebody who is experiencing hardship, even if it is somebody far away, they still feel sorry for them and want to help. But what about themselves? They experience difficulties in their own lives. If we are not in a position to help somebody, we must assume an equanimous attitude. This is how upekkhā, equanimity, resolves such situations, thereby cultivating peacefulness and coolness in our hearts. This is how those who wish to transform their minds to be like those of a Brahma god have to practise.

However, if you want to become an ariya-puggala,9 a Noble One, you must cultivate the path of sīla, samādhi and paññā, moral virtue, concentration and wisdom. To start with, a firm foundation of sīla must be established within the heart. For laypeople this can be done by keeping the five precepts, or if you are particularly determined you might try keeping the eight precepts.10 Novice monks keep ten precepts, while fully ordained monks must observe 227 training rules.. The observance of moral precepts creates a strong foundation on which we can establish our concentration practice. The strength of concentration in turn gives rise to sati-paññā, mindfulness and wisdom. Once mindfulness and wisdom have arisen, the transcendent path that leads to liberation becomes established. The path is none other than sīla, samādhi and paññā, which we develop in order to eradicate greed, anger, sexual lust and delusion from our minds. All three path factors must be present for this to be effective. Moral virtue alone cannot take us along the path; neither can wisdom and moral virtue without concentration.

Some people like to think that all they need for insight to arise is to do jit or watch the mind in the present moment to see the thoughts and emotions as they arise and cease. But in fact they are not insightfully seeing the arising and ceasing; it is only a momentary or superficial kind of seeing, because it doesn’t take very long before the mind returns to being occupied with all its thoughts and emotions again. This method cannot lead to a state of emptiness of mind, that is, a state where the mind is free of thoughts and emotion. True insight, vipassanā, depends on the working of mindfulness and wisdom to contemplate phenomena and let them go.11 The aim of the contemplation is to see the impermanence and absence of self of both the physical body and the thoughts and emotions.

The practice of sīla alone does not give the mind enough strength to generate mindfulness and wisdom. We have to develop concentration because this is what strengthens mindfulness and wisdom, making the mind stronger and more resolute so that we can clearly examine and cut away the defilements. A mind strengthened by concentration will possess the mindfulness and wisdom to deal with any suffering or discontent that arises from the emotions of greed, anger and sexual desire, by contemplating and examining them to see their impermanence and thereby letting them go. On an external level the emotion of greed can be let go by practising generosity, learning to give as a way of developing one’s dāna12 pāramī. We cultivate this quality so as to not allow any miserly or ungenerous tendencies to remain within our hearts. To let go of anger requires us to develop goodwill and forgiveness towards one another. Sensual desire or feelings of satisfaction and dissatisfaction regarding our sensory contacts can be let go of through contemplating to see the impermanence of all forms, sounds, odours, flavours and bodily

sensations.

Sexual desire is to be countered by reflecting on the body, in particular one’s own body, to see that it is impermanent and devoid of any entity that could be regarded as the self.

Body contemplation is a skill that we have to develop because it is the way to counteract sexual desire. Sexual desire is a natural feeling shared by humans and other animals alike, regardless of whether they are male or female. Still, we need to know how to keep this emotion under control, so that it remains within the bounds of correct moral behaviour. If you are married or in a stable relationship, you should be content with the partner you already have. Those who are single shouldn’t deceive or mistreat the heart of another. This is the extent to which we must control our minds, and it can be done if we develop concentration. That’s the way to make our hearts cool and peaceful. In addition, we should investigate our body by contemplating one of several themes: the 32 parts;13 the asubha14 (unattractive) nature of the body; or the four primary elements that make up a human body: earth, water, air and fire. Such reflections provide our mindfulness and wisdom with a means to counter the mental defilements by not allowing them to develop to such an extent that we overstep the limits of correct moral behaviour.

All the trouble and disorder that we see in our societies are due to the lack of virtuous, disciplined behaviour. When sexual desire arises in the heart of someone lacking in morals, such a person is quite capable of physically harming someone else or doing things that will abuse and hurt the heart of another person. However, people who have moral principles will not go about deceiving members of the opposite sex. If we're without moral restraint, we’re done for! Then at any time when the defilements arise in such force that we become blinded by them, the result is only shame for ourselves and grief for others and their families. People tend to be selfish, especially those who deceive the opposite sex. Just think how you would feel if some man were to deceive your sister; would you like that? If we think just this much, we already know the answer. What about your brother? If some woman were to be untruthful to him, would you approve? Nobody would, would they? Just ask your own heart and you know. When the mental defilements are in control they will always misguide us, misleading us to think, speak or act in bad and immoral ways.

The reason I’m telling you to develop concentration is because you are not practising enough; you have to give more time to it than you already are doing. It is something we have to do because if we’re lacking in mindfulness and wisdom, the instant that bad or unskilful thoughts arise we will speak and behave improperly or unskilfully. However, if we practise concentration our mindfulness will become stronger and better established, giving us the patience and self-control to endure all our moods and thoughts. Concentration also provides us with the skilful means needed to reflect on any unwholesome thoughts and to let them go from the mind. When our mindfulness and concentration are weak, the mind will blend together with its moods and thoughts so much that whatever the mood, the mind will assume the same tone; they will become one and the same until the two cannot be told apart. When the eyes see forms or the ears hear sounds, a whole flow of mental impressions will arise within the mind, together with their subsequent emotions. When the mind perceives this flow of mental impressions, it will be unable to remain still because it lacks mindfulness and concentration. As a result the mind will flow together with the stream of thoughts and emotions, because it believes they are the actual mind itself. This makes the mind so familiar with all its emotions that it attaches to and identifies with them as being the self.

We have been deceived by the contents of our mind, the thoughts, moods and emotions, for who knows how many lifetimes, right up to the present. It has become normal for us to think that our thoughts and mental states are the mind, but they definitely are not. Nevertheless, the mind likes to think they are. That’s a delusion. The flow of thoughts and emotions is just conditions or states of mind, but the mind attaches to this flow, believing it to be the mind itself. This being so, whenever we experience feelings of greed, anger, satisfaction or dissatisfaction, we will consider the emotion to be the self, to be ‘me’. We continue to suffer for our entire lives, all because the mind believes its thoughts and emotions are the self. What we need, therefore, is to have mindfulness and wisdom contemplate our moods and emotions to see their impermanence as they arise and cease. We must try to separate the mind from the stream of thoughts and emotions, but to do so we have to develop mindfulness and concentration. Once the mind is peaceful and concentrated, it will naturally separate from this stream all by itself and remain detached or neutral whenever thoughts and emotions arise. As a consequence, when the eyes see forms, the feelings of either attraction or aversion that arise will not affect the mind. The mind will remain unmoved, settled in the present moment.15

When the mind perceives a form such as another person, this may arouse feelings of attraction within the mind. We must use our mindfulness and wisdom to reflect on that person with the aim of seeing the impermanence of their body. Alternatively, we could use the asubha contemplations to reflect on the inherent unattractiveness of their body. Owing to the strength of mindfulness and concentration, the mind will offer no resistance to our reflections; instead it will accept them as being the truth and thereby remain settled in the present moment. If feelings of aversion arise towards that person, we can reflect on the impermanence of their body and our mind will again remain in the present. If the form is a material object, we can reflect on it to see that its nature is to change and deteriorate. This will once again keep the mind in the present, because the contemplation will abandon the feeling of attraction or aversion which arose towards that object. However, we tend not to see things in line with the truth, and so when we see a form and it gives rise to attraction, our thoughts begin to proliferate about that form, generating more feelings of attraction, desire and lust. This all happens because the mind moves from its base of neutrality. This is why I’m telling you to be diligent in your meditation practice. Concentration must be developed.

If you want to make your body strong so it can lift very heavy objects weighing 30 to 40 kilos, you will need to play sports or do physical exercise. Once the body is strong you will be able to lift any heavy objects with ease. With our minds it is just the same. They are in a weak condition at present, not strong enough to lift up and throw off all the greed, anger, restlessness and delusion that are weighing them down. If we hope to make our minds stronger, they must be exercised through practising concentration. Once we have made our minds strong, when we experience sensory impressions and the subsequent feelings of pleasure or displeasure, our mindfulness and wisdom will have the strength to push those feelings aside and let them go. Otherwise our moods and emotions will just keep piling up on the mind and maintaining it in a weak condition. Have you ever noticed that sometimes your heart has little strength, causing you to be too soft-hearted and submissive, as well as lacking in resolve, purpose, and the strength to stick to your word or to do the work of building up the spiritual perfections? This is all due to the mind being weak. We really must do everything we can to strengthen the mind and all the spiritual perfections. Go about it gradually, little by little, and you will build up the strength of your mind. A strong mind has the patience and self-control to endure all thoughts and emotions. Mindfulness and wisdom will also reflect on them so as to let them go from the mind.

This is why I keep saying that you must develop concentration. You eat three or four meals a day to nourish your body, and yet you rarely think to nourish your heart, your mind. Rather than sit in meditation just once, you make all kinds of excuses as to why you don’t have time. Ajahn Chah would ask people who liked to make such excuses: ‘Do you have the time to breathe?’ He also said: ‘If you have time to breathe, you have time to meditate’, meaning that in truth we always have the time to focus our mindfulness on the breath. The wise know that the practice can be done at all times. Nevertheless, people always say they are too busy with their work and duties, with no time to practise meditation. They work seven to eight hours a day, maybe more if they do overtime, but they have no time to meditate. They can find the time to work seven or eight hours a day, yet they won’t give one hour or even half an hour to the practice of meditation. And why is that? It’s simple really. For our work we are paid at the end of each week or month: we get something for our effort. However, we don’t see anything tangible coming from the practice of meditation. People tend to think only about seeking out material wealth and possessions, with the hope of being wealthy and having a strong, secure financial standing, but when the body stops breathing all our wealth is merely just that much; it ends right there. If we breathe in but don’t breathe out, or breathe out and fail to breathe in again, that’s it, the end!

Is our wealth truly ours? At the time of death can we take it with us? And our bodies, can we take them with us? Not long after death the body is either cremated to ashes or perhaps buried, as the Chinese tend to do. And once buried, what becomes of it? It decomposes, returning to its elemental form of earth, water, air and fire, with nothing remaining. We cannot take anything with us! That’s why I tell you to contemplate on the imminence of death. Don’t go indulging too much in the world. Anyone living in the world should have the mindfulness and wisdom to know that all forms of worldly happiness merely serve to ease our suffering and unhappiness temporarily. It’s just a trifle of happiness; it is certainly not the kind of happiness that can bring the greed, anger and suffering within our hearts to their cessation. However, to view things in this way requires wisdom.

The Lord Buddha taught us to cultivate the spiritual perfections so as to bring an end to all the greed, anger and suffering in our hearts. It is through the practice of his teaching, through internalizing it, that we can develop our minds. The heart is made good by practising generosity, observing the moral precepts, developing concentration and cultivating wisdom. This and only this can bring an end to the suffering and unhappiness in our hearts. The seeking of external or worldly wealth cannot do this, it merely eases them. People have suffering in their hearts but they don’t see it. When we are unhappy or feel uneasy, we try to change our mood by doing something, such as going out for some fun or arranging to meet up with friends somewhere, or perhaps we go to the movies, or go on a holiday. But as soon as we finish doing all that and go back home, we experience the suffering once again because we didn’t correct the problem in the right place. All we did was run away from it, avoid it temporarily, without actually remedying our heart in any way. This is how people live and behave.

The mental defilements are extremely clever at trapping the hearts of people. This is what they call Māra’s16 snare. And what is Māra’s snare? It is the temptation or seductiveness of forms, sounds, odours, flavours, physical sensations and material objects. All these will charm and allure the mind into the snare. It’s no different from the traps and nets used to catch animals. The snare is set and at birth we become ensnared. It is Māra tempting us to seek pleasure from sensory experience and from wealth, status and praise. This is the snare that the kilesas have laid and trapped us in. Once caught, we can’t set ourselves free because we take pleasure and delight in the sensory world. As a result we are unable to leave samsāra17 because the mind is content to be reborn into each lifetime. There happen to be billions living here in this world because they are content to be reborn again.

If you were to tell all those people to follow the path taught by the Buddha, they wouldn’t be interested. Thailand is generally regarded as a Buddhist country, as 90% of its population is Buddhist. Even so, people are not truly interested in their religion. They are Buddhist in name only. Buddhism is not the official state religion in Thailand, but the vast majority of Thais consider their country to be a Buddhist nation. But what do people actually believe in? One minute they are robbing and mugging each other, the next they are cheating and lying. Such people have very few if any morals. It's actually a rather small number of people who are willing to come to monasteries or to make offerings and observe the moral precepts. Those who come and listen to a Dhamma18 talk are also very few; you get maybe ten, 20 or possibly up to a hundred people coming to listen. On the other hand, if you were to organize a rock concert people would come by the thousands! Then they'd jump about to the music like vultures and crows, or maybe it’s more like hungry ghosts (petas). I really don't know what you would call them. What they’re doing is merely indulging in their emotions.

Ajahn Chah would say: ‘Those who indulge in the world19 are deluded by their emotions; those who indulge in their emotions are deluded by the world.’ Those who are deluded by the world are those who indulge in their emotions or feelings, especially feelings of pleasure and happiness. When we indulge in those feelings we become stuck in the world. Actually the state of indulging and being stuck are exactly the same, but people seldom see this. By failing to see the dukkha or inherent unsatisfactoriness of this situation we become stuck on worldly pleasures and therefore unable to find a way out of this predicament. To transcend suffering we must first see or comprehend it. When we do so, our mindfulness and wisdom will search out its cause and a way to bring it to cessation.

Nowadays people are carrying around so much suffering that it’s almost killing them, and still they don’t see it. The Buddha didn’t actually have to experience any real suffering, yet his wisdom was still able to comprehend its existence. Why didn’t he have to suffer? Being human is dukkha, right? But not for the Buddha. He was born into royalty, with many attendants serving him. He could do as he pleased, thus encountering very little suffering or discontent in his life. There were only happiness and sensual pleasures, with the joy of having his every wish fulfilled. Despite all this, deep within his heart he comprehended suffering when he realized that beings are incapable of escaping ageing, sickness and death.

One day the Buddha travelled out of the palace. He was curious to see what the lives of ordinary folk were like. His own life in the palace was surrounded by beautiful objects and many beautiful royal concubines and maidservants. He first came across an old and decrepit man. Just seeing this much causes a wise person to begin reflecting. He enquired of himself: ‘Is it thus that we humans must grow old?’ Then he encountered a sick person lying at the side of the road. He asked himself: ‘Why is it that I am strong, healthy and fresh in complexion?’ He realized: ‘One day I too will not escape from sickness and pain.’ Lastly he saw a dead body being cremated and realized that all beings must die. He saw ageing, sickness and death and considered them dukkha, suffering. Even though he himself was not yet old, sick or near death, his wisdom could still see this clearly. He had seen suffering and desired to seek out its cause. Had he remained as he was, caught in Māra’s snare, he would have been unable to find the cause of suffering. Instead he decided to seek liberation, freedom from suffering. He fled the royal palace on a quest for the transcendence of suffering, searching for its fundamental cause and the path that leads to its cessation. He travelled about trying different practices until he met with two hermits, Alara Kalama and Udaka Ramaputta. They had both developed the meditative absorptions to their highest level, and instructed the Buddha accordingly until he too had reached their same level. But still he could see that concentration alone was not the path for the transcendence of suffering; while it temporarily suppressed thoughts and emotions, it did not extinguish the mental defilements. Thus he searched on until he realized the Noble Eightfold Path; that is, sīla, samādhi and paññā, the development of moral virtue, concentration and wisdom. He had discovered the Middle Way for the abandoning of the mental defilements.

For us it’s quite the opposite. We can work all day in the blazing sun or pouring rain, even be up working on roofs, exposed to the elements and enduring great hardships, and yet we still don’t see suffering. What’s the matter with us? The wise ones, the noble or spiritually attained ones, can perceive suffering with their wisdom without having to experience it as such. However, the vast majority of people don’t see suffering because they’re so completely attached to their comforts and pleasures. For instance, here in Thailand we are blessed with the teaching of the Lord Buddha, and yet people pay it no attention. If they are not interested in his teaching and have no intention of taking it up and putting it into practice, it can’t be used to help ease their suffering and unhappiness. They’re no different from chickens foraging for food, scraping away looking for worms and ants; if they were to come across a diamond they would kick it away because it’s not food. People are just the same. They search for happiness and pleasure through their five senses, yet they turn their backs on the Dhamma. The Dhamma is of immense value, but they think otherwise; they consider it to be of no use at all. They’re more inclined to think: ‘Going out for some fun is better than that’, or ‘Not having moral principles and restraint appears to be a much more desirable option’; or maybe they think: ‘Getting drunk is more appealing than that.’ This is the happiness of deluded people.

This is why I maintain that if you don’t develop concentration you will never progress in your Dhamma practice. You have to start developing it. People are mostly too lazy to keep up a regular meditation practice. They may have given it a try but didn’t achieve any peace, so they look for an easier way to practise and become content with just ‘watching the mind’. This is nice and easy to do, and they believe it will also rid the mind of the mental defilements. Developing concentration is something they don’t want to do because their previous efforts were unsuccessful; they achieved no peace or stillness because their minds were restlessly thinking. So they turn to watching the mind, or more correctly, watching its thoughts and emotions, because it’s much easier. Go ahead! Watch them all day if you like, but this will never cause them to cease, it doesn’t get rid of them. The stream of emotions arising and ceasing can pass by uninterrupted only when our mindfulness has the strength to remain objective. Otherwise, as soon as we have a lapse of mindfulness the mind will drift off, indulging in its emotions again. Today we have experienced all kinds of sensory impressions and the emotions of liking and disliking that arose dependent on them. Now they have all passed by. But tomorrow there will be new impressions: new images, sounds, odours, tastes and bodily sensations, and their subsequent feelings. The day after tomorrow will be the same, and so on. The mind will patiently and continuously let them go, but they will never cease because their cause isn’t being suppressed, they’re not being dealt with at their source.

What causes moods or emotions of greed, anger or sexual attraction to arise? It’s the mind’s deluded attachment to one’s own body as being one’s ‘self’ or belonging to oneself that causes them to arise. It is the sense of self which creates the defilements of greed, anger and sexual attraction, and it all starts with the body. To counter this habitual flow of the mind, we need to contemplate the body. To do so will uproot all identification with the body as being oneself. However, body contemplation cannot be done if the mind is lacking in the mental strength derived from concentration. If our concentration is weak, our mindfulness and wisdom will not be sharp enough to do their work. Concentration is like a knife. If we use a blunt knife and try to cut branches and vines, will it cut through them? Our minds are just the same. Without concentration, our mindfulness and wisdom are not sharp enough to penetrate their object of contemplation. So what do we do when we know we are in possession of a blunt knife? Sharpen it, of course! Mindfulness and wisdom are sharpened by developing concentration. Ordinary intelligence is not as sharp as wisdom. People who lack moral virtue can possess intelligence, but not wisdom. If we want our intelligence to have the sharpness of wisdom, we must observe the moral precepts and practise concentration. It is the continual practising of concentration that does the sharpening. Once our faculties of mindfulness and wisdom are sharp, they will probe into all our sensory experiences with the aim of seeing the impermanence of forms, sounds, odours, tastes and body sensations. Everything will be taken up for examination. Sati-paññā, mindfulness and wisdom, originate from the power of concentration. Concentration is the strength or the energy that supports mindfulness and wisdom.

Just think of a cell phone. If we keep using it the battery will run down until eventually it is flat. We then have to recharge it. We use the phone and then recharge it, and with a continual charge the battery becomes full, ready for use again. If we don’t practise concentration the mind will just keep on thinking the whole day long about work, family hassles or the many other little things that it likes to think about. However, all this thinking leaves the mind in a weak and tired state. In other words its battery has been drained; mindfulness and wisdom have been drained of their energy. So we have to recharge our battery, and we do this by giving the mind some rest, resting it in the peacefulness of concentration. Having rested the mind will be energized, and mindfulness and wisdom will once again be able to deal with any problems.

In truth, there isn’t much to the practice of Buddhism. There’s no short cut or fast track; there is only the Middle Way as taught by the Buddha. It’s the most direct path, but it can’t be considered a short cut. The Buddha’s path can be walked by everyone, for he taught only one path of practice, the Middle Way. The path of practice for laypeople is to cultivate goodness and generosity, observe the moral precepts, practice concentration and cultivate the mind20 so as to give rise to mindfulness, wisdom and right view. People often like to cite individuals who have made rapid progress in meditation practice. But why was it rapid? Because those people had already developed the spiritual perfections to a great extent in their previous lives, and so in this present life their practice progressed very quickly. And why is someone’s practice slow? Because in their past lives they didn’t cultivate the perfections to any great extent, and so in the present life they have to do a tremendous amount of practice, thus awakening to the Dhamma more slowly. This is how it works.

We should never dispense with the fundamental guiding principles that the Buddha taught. Actually, there isn’t a great deal at all to Buddhism. Even if we were to expand on his teaching, going out to the furthest reaches of the universe, we humans would still only have a body, speech and mind. This is all there is to the Buddhist universe. It can be narrowed down further to the body and the mind, and ultimately to just the mind alone. And so why must we contemplate the body? Because the mind clings to the body as being who we are, or our self. Hence we have to let it go. Once the body has been attached to or identified with as being oneself, the mind will not readily want to let go. However, this state of attachment causes nothing but suffering for us and so we have to teach the mind to let go.

And in what way does the mind cling to the body? At present you consider your body to be yourself or as belonging to you. But at any moment you can start to feel unwell, perhaps with a headache or stomach-ache. When this happens, why don’t you politely ask your body to please get better? Go ahead, try telling it to get better. Try telling it: ‘I always take such good care of you and give you three or four good meals a day. Sometimes I even go to department stores to buy good clothing to dress you with. Please don’t betray me like this.’ But does it listen to you? You can order it to get well, but it won’t do as you say. Actually, it won’t believe anything you say. Our mindfulness and wisdom therefore have to become wise to the body, and realize that the body is not the mind and the mind not the body. The body is not the self, that’s for certain, because it doesn’t obey us. We have to teach the mind gradually in this way, employing a superficial approach to vipassanā. It’s not that vipassanā can be practised only while sitting or walking in meditation; contemplation can be done at any time. Whenever you’re feeling ill, just ask yourself: ‘Why can’t I tell the body to get better?’ If you can’t order it to get better, that shows it isn’t ‘you’ or yours. Actually, whether it gets better or not is the doctor’s job; your job is just to take all the necessary care of it that you can. Put your mind at ease like this; let go of the body. However, that is difficult to do because to do so depends on the development of moral virtue, concentration and wisdom.

Apply your wisdom by contemplating the body frequently and the mind will gradually begin to let go of its hold on the body. It is similar to having a boat that you want to row across an ocean or a river. Having pushed the boat away from its mooring, you start to row. After a while you notice that the boat is leaking, so you take a bucket and start bailing out the water. Later the leaks become even more serious, and so you have to get some sealant and start making repairs to patch and stop the leaks. Once this is done you continue rowing. You depend solely on the boat to take you across to the other shore. Your boat is actually no different from your body. The mind depends on the body and so it must be cared for in times of sickness. Why should you care for it? Because you rely on it to support you in the practice of cultivating goodness and the spiritual perfections. You should care for your body as long as you are able to do so. Eventually, when it is beset by illness and disease which are too much for it to withstand any longer, the mind must let it go its natural way. It’s as if you are sailing in a badly leaking boat; no matter how much you row, it will never take you to the distant shore because it is gradually sinking until it goes under. You then have to look for another boat, a new boat to continue your journey. In other words, on the death of the body if the mind still has defilements remaining it will search for a new body.

The body is impermanent just like the boat, but if it can still be cared for we must do so accordingly. This is why we contemplate death, because to do so urges us to develop goodness and observe the moral precepts. The practice of meditation is something that we must do now, while our bodies are still strong and healthy. Practise contemplating your body in the manner that I’ve been describing to you. You are already observing the precepts, but you’re not doing nearly enough concentration practice. You have to strengthen your pāramīs of morality and concentration.21 This is how it works; they have to be gradually strengthened. At present you would all be considered to be middle-aged, and with the passing of time you will keep getting older. Can you tell your body to return to being youthful again? Oh, but you take such good care of it by giving it three or four meals a day. When it wants to eat fine delicious foods you go and buy them. You do all this for your body because the mind is infatuated with it. You even buy good clothing for it to wear, but as soon as the body starts getting old and you tell it to be youthful again, it can’t or it won’t do so! Really, it’s enough to make you feel indignant. All that good care we give the body, but when it is about to die and we try telling it not to, pleading with it to live longer, it won’t listen to a word we say. And why won’t it obey us? Because the body is nothing more than a mass of naturally existing elements, earth, water, air and fire, which have temporarily joined together. The earth element has no knowledge of anything at all. Likewise with water, air and fire: they are totally ignorant entities. They have merely joined together to make up a body; it’s nothing more than that. One day the body will finally inhale but fail to exhale, or exhale without inhaling again. Subsequently the heart will stop beating and the mind will then travel out from the body.

What happens when the breath, the air element, has gone? The body’s warmth, the fire element, begins to disappear, as it can no longer sustain itself without the air element. Initially, all four elements of earth, water, air and fire exist together. Once the air element has gone, the fire element will also leave the body. The body then begins to cool; corpses are rather cold, you know. Some days after the fire element has gone out, the earth and water elements begin to react by causing the corpse to gradually fester and bloat, just like a balloon. Then after a period of time it starts to deflate as the water element, blood etc., begins to slowly seep out, leaving the body to decay and sink inwards. The remaining earth element, that is, any bodily parts that are hard or have form, such as head and body hair, nails, teeth, skin, bones and sinews, etc., finally break down and crumble away. The earth element has never proclaimed it is the self. It doesn’t even know that it’s a part of a body. Instead, it is we, or rather our minds, that attach to it and take it to be the self.

What is head hair anyway? Regardless of whether it is long or short, it is just the earth element, but we consider it to be our own, ourselves, and so we keep it clean and give it lots of attention and care. You have probably combed your hair and noticed that two or three hairs have fallen out. When you next see this, try reflecting on them by asking yourself: ‘Are these hairs really who I am, my “self”?’ When you put them down they are motionless, completely lifeless, unable to go anywhere at all. They are simply the earth element. Actually, hair is rather complex, being comprised of all four elements, but it is normally categorized as being the earth element.

Hair is a lifeless object, and yet when it’s on our heads we think it’s attractive, often looking at it in the mirror, admiring its beauty. But would you believe that your hair is intrinsically dirty? Here’s something you can try. When your mother is making a stew, say: ‘Just a minute, I have something absolutely divine that I would like to add to it.’ Then put in a pinch of seasoning powder, followed by your divine ingredient—a small handful of your hair, freshly taken from your comb. Now, would that be an appetizing stew or not? What does this show you? It should show you that hair is something that is dirty and distasteful, right? If it were truly clean you could say to yourself: ‘This food is excellent.’ However, it’s quite the opposite, because we feel that hair in our food is something most sickening.

If we don’t wash our hair for three or four days it becomes greasy due to the oil coming out from the scalp. We all consider this oil to be rather disgusting, even though it comes from our bodies. Our hair always has to be washed for us to feel good and look clean. Our bodies are no different from our hair. Believe me, whether you work all day long, play sports or simply come here to the monastery, come the evening when you arrive home, you have to shower to cleanse your body. It requires soap to remove the dirty, sweaty grime that has exuded from our skin. The clothing that we wear is at first clean and freshly ironed, but come the evening, just try giving it a sniff to see what it’s like. Whether one is male or female makes no difference at all, the body is inherently dirty. I’m just speaking rather matter-of-factly with you, it’s nothing overly objectionable. But go on, just try giving your clothing a sniff; it’s really quite repelling. This shows us that the body, whether male or female, is in a perpetual state of decay, but we fail to see this. Instead we see only the present condition of somebody else’s skin and look on it as being attractive. And so when our eyes see other people they focus on their skin, because we see beauty there. We get stuck right there, stuck on the body as it is at present.

How do the Noble Ones, those who have attained to one of the four levels of enlightenment, deal with this problem? If they are determined to intensify their practice so that they develop or walk the path towards a higher attainment, they will try to perceive right through the person they are looking at by superimposing an image of that very same person in the ripeness of old age, and finally as a corpse. They do this with the aim of seeing the impermanence and selfless nature of the body. As a result their minds will be equanimous and feel no attraction towards the other person. Others may take the approach of instantly bringing an asubha image into their minds by visualizing the intrinsic unattractiveness of the other person’s body, regardless of whether it is male or female. As a result their minds will rest in equanimity, feeling no attraction whatsoever towards that person’s body. These are the methods that the Noble Ones will use to counter the mental defilements.

Actually there are many methods, but we fail to make use of them. Instead we do quite the opposite by allowing our minds to proliferate about the body we are looking at. This only gives rise to more defilement. The magga (the path of practice that leads to liberation) of one who upholds moral virtue and leads a celibate22 life is to further develop sīla, samādhi and paññā so as to make these factors strong and stable. These three factors can be considered as three very strong armed forces, and when they join together they become one mighty military force. The Noble Ones possess this great force and so they are able to bring an asubha image to mind immediately. However, people lacking in moral virtue are completely unable to do this, because the sight of other people brings up nothing but defilements in their minds. If greed arises they indulge in it, knowing no limits. And if anger arises,they allow their minds to be consumed by it. Ultimately the power of the mental defilements can even cause people to physically harm or kill one another.

As I’ve already said, there isn’t much at all to Buddhism. Even if we were to expand on the teaching, taking it to the outermost reaches of the universe, Buddhism would still only be about the body, speech and mind. These three can be further narrowed down to leave only the mind. The kilesas exist solely within the mind and nowhere else. They do not reside in one’s house, one’s wealth and possessions or any other location. They are right here in our hearts and wherever we go they go too. It all comes down to the mind, and if we are to remedy the defilements it must be done within the mind. In Buddhism we contemplate only the body and the mind, that’s all there is to it. Body contemplation is practised so as to see the impermanence of the body, and that there is no existence of an abiding self to be found anywhere within it. In doing so we will come to the realization that the body is not the mind and the mind is not the body. Our thoughts and emotions are of the very same nature as the body: impermanent and devoid of any self entity.

All of us wish for happiness, so why is it that we still experience unhappiness and suffering? Whenever you are feeling unhappy or discontented, do not take these emotions to be your mind, because they certainly are not. Try taking a step back from them by making your mind perceive them as not being the mind itself. If you experience an emotion of greed or anger, satisfaction or dissatisfaction, try telling yourself: ‘This is just an emotion, it isn’t my mind, it’s not me. It’s merely an impermanent condition that has arisen and must by nature cease.’ We have to start by having mindfulness established in the present moment, so that we can work at filtering out all the unwholesome things from our minds. As laypeople you must set up mindfulness from the moment you wake in the morning and maintain it throughout the day while going about your work and duties. Always try to have mindfulness in control of your mind by keeping watch over your thoughts and emotions. Those who keep a vigilant watch on their minds will attain release from Māra’s snare.

Keeping a careful watch on the mind means always trying to maintain mindfulness, regardless of whether one is standing, walking, sitting, lying down or doing some other activity. Whenever mindfulness slips away, and it will do more often than not, we must re-establish it. The best way to do this is by bringing it to focus on a meditation object. For example, we can be attentive to the breathing or the repetition of the meditation word ‘Buddho’. When you realize that you have little mindfulness because your mind keeps wandering away with all its restless thoughts and emotions, bring your mindfulness to focus on the breath. Direct your attention to the tip of your nose and simply know when the breath comes in and goes out. Just be attentive to this alone. It isn’t that we can watch the breath only while practising sitting or walking meditation. Outside formal meditation practice, regardless of what you’re doing, as soon as you recognize your mind is unfocused and overly active bring your attention to your breath. Focus on it for three to five minutes, and all the restless thinking will cease because you are no longer taking any interest in it; your interest is now with the breath instead. If you find watching your breath uncomfortable, try recollecting the Buddha by adopting a constant internal recitation of the word ‘Buddho, Buddho, Buddho'. Focus your mindfulness right there and the mind will cease its preoccupation with all its defiled thoughts. By temporarily cutting off the flow of thoughts and emotions mindfulness can be established. Practising in this way is called samatha23 meditation.

Some practitioners have already developed good, strong mindfulness. As soon as they see a form or hear a sound, it gives rise to a feeling, for example, attraction or pleasure. This feeling in turn activates the thinking processes. And do you know what they do in this situation? Once they are aware that a thought or emotion has arisen, they stop their recitation of ‘Buddho’ or watching the breath. On sensory contact, a fragment of their mind-stream goes out to receive or link up with the stream of emotions and thoughts; it’s a habitual process. However, the remainder of their mind-stream stays fast in the present moment because they have previously developed mindfulness and concentration. They then direct their wisdom to destroy the stream of emotions and thoughts by contemplating their impermanence and absence of self. This causes the flow to cease, to drop away. It’s analogous to somebody sending up a flying target which we immediately shoot at—bang!—and it falls down. We do exactly the same within our mind. As soon as a flow of sensory impressions contacts the mind, giving rise to feelings such as attraction or pleasure, a fragment of our mind-stream will go out to join with them. However, mindfulness and wisdom will perceive this movement of mind and therefore race out to destroy it at its source, by contemplating the impermanence of the particular form, sound, odour, flavour or bodily sensation that caused the feeling to arise. Once the mind movement is destroyed, mindfulness will again return to the present moment.

If mindfulness and wisdom are lacking in strength, that is to say, if one’s knife is blunt, it must be sharpened. When our faculties of mindfulness and wisdom are weak they are incapable of contemplating, because there will always be a residue of thoughts and emotions lingering in the mind. Don’t go giving those emotions and thoughts any attention at all. Instead just take up the recitation of 'Buddho'. A firm and well-founded mind will have only one object in its awareness at any one time, so through taking up and firmly maintaining the recitation of ‘Buddho’, all other thoughts and emotions will cease. Our thoughts, moods and emotions are only conditions or states of mind which shadow the mind and work to deceive it. If we develop concentration we will gradually be able to see this deception, because our minds will naturally develop and become sharper.

As laypeople you should start by trying to sift out any bad or unwholesome thoughts from your minds. Once mindfulness is well established any unwholesome thoughts will easily be perceived. Whenever they do arise, you must use whatever skilful means you can to let them go. If your attempt proves not to be strong or incisive enough to deal with them, re-establish your mindfulness on a meditation object such as ‘Buddho'. Recite ‘Buddho’ or watch your breath for three to five minutes to bring the mind back to the present moment. The instant the thought or mood disappears, you can drop the recitation of ‘Buddho’ or watching the breath, and just have mindfulness guarding and controlling the mind, keeping it established in the present moment. After half an hour or an hour those particular thoughts or moods may re-emerge, sneaking back into the mind again. If so, try giving your sati-paññā another go at contemplating, because this time it may be strong enough to deal effectively with them. But should this still prove not to be the case, put the thoughts or emotions aside by returning to the recitation of ‘Buddho’; keep them aside for as long as it takes to develop sufficient strength of mind to take them up for further contemplation. This is how it works. Just keep on practising like this. Always try to be mindful no matter what your bodily posture or activity may be, and whenever mindfulness lapses, re-establish it.

When you have free time, use it to sit formally in meditation. If you begin to ache or feel stiff and sore from sitting, change to walking meditation. You have to practise a lot, really develop the practice, because at present you’re doing far too little! Those who study or practise the method of Venerable Pramote24 tend to do very little formal meditation practice. Many of his disciples who come here don’t seem to see the benefit of developing concentration. Some of them say their minds are so lacking in peace that they can hardly concentrate. When I ask them how many hours a day they practise sitting in meditation, they reply: '15 minutes', or maybe: '30 minutes' for some. They wish for peacefulness, yet practise so little owing to their lack of patience and endurance. They are unwilling to force themselves to continue when the practice becomes difficult. If I ask whether they practise every day, they generally reply: 'No.' It’s similar to somebody investing ten dollars and expecting a return of 10,000! If they invested 10,000 dollars with the expectation of receiving a return of several hundred or maybe one thousand, that would be a bit more realistic. They sit in mediation for ten minutes and if their minds don't quieten down they give up. When I ask some of them: ‘Why don’t you sit in meditation?’ they usually reply that they don’t want to focus their awareness too intensely on one given object for fear of becoming attached to the peacefulness of concentration and getting stuck there, unable to progress any further. They’re not yet even able to concentrate their minds, but already they are afraid of getting stuck by becoming addicted to the peacefulness of concentration!

So how should you go about focusing your awareness? Simply bring your mindfulness to focus on your meditation object, for example, the meditation word ‘Buddho, Buddho’. Reciting ‘Buddho’ is no different from when we were at school and had to memorize simple English vocabulary by rote. I didn’t find that stressful in any way at all, so why would repeating ‘Buddho’ be stressful? We gently focus the mind on the internal recitation of ‘Buddho’ to make the mind cool and peaceful. Before long the mind becomes cool and light with the rapture and happiness of concentration. This is how it develops.

The mental defilements (kilesas) are really smart when they tell us not to focus our attention on a meditation object out of fear of becoming a bit strange or unhinged. They’re even so clever that as soon as the mind starts to think up ways to counteract them, they will forbid our wisdom faculty to take any such action or interfere with the natural flow of the mind in any way whatsoever. But why is it that greed and desire are nevertheless allowed to interfere? Why is anger allowed to interfere? And why is sexual lust allowed to interfere and become involved in this natural flow, but mindfulness and wisdom are not? ‘Don’t interfere’, the kilesas keep telling us. ‘Just let them be.’ These defilements are really so much smarter and wiser then we humans! If we even just think of developing concentration so that we can start to counter the kilesas, they tell us not to practise a lot, saying that we will become attached to the peacefulness of concentration or even maybe go a little mad. They don’t want us to discover the way to peacefulness, or to tap into this source of great mental power that gives rise to mindfulness and wisdom. So as soon as the mind thinks to employ its wisdom faculty to investigate and counter the defilements, the kilesas will forbid us to do so by telling us that this intention to investigate or contemplate is itself a defilement, a mere proliferation of thoughts stemming from the defilements. Believe me, if you take this approach to Dhamma practice you’re as good as dead! You will progress no further than where you already are. Those who practise like this have lost the way. They don’t know the way of practice. If someone who can’t swim teaches others how to swim they will all drown together. Let the blind lead the way and together we will all drop into the abyss.

It is essential for us to develop right view or correct understanding (sammā-ditthi). There’s no need to go seeking out many different teachers or other Buddhist groups and sects, because the teaching of the Buddha is still here with us, it’s still here in this world. He taught just one path of practice for everyone: the Middle Way. The heart of Buddhism is to refrain from all wrong-doing and to cultivate the good.25 And how do we go about cultivating goodness? As laypeople you should practise generosity, cultivate everything good as best you can, observe the moral precepts and develop concentration. And why? Because to do so gives rise to mindfulness, wisdom and right view, so that we can then let go of the kilesas and thus purify our hearts. The essence of the Buddha’s teaching is just this much; to refrain from all evil and to develop all that is good. And what’s the reason for developing goodness? We do so in order to cleanse and purify our hearts. You don’t have to search elsewhere for short cuts, because there aren’t any. There is just this one path, the Middle Way, which is completely balanced and ‘just right’. As I already said, those who in their previous lives have greatly matured the pāramī will be able to realize the Dhamma26 here in this present life without having to do a great deal of practice. However, those who in their past lives made very little effort to build up those perfections will have to practise hard in this present lifetime and meet with great difficulty along the way. We therefore need to be patient and have endurance. Don’t just give up when your meditation is not peaceful. Such an attitude is not acceptable.

Ajahn Chah would say: ‘Take it to the absolute end.27 Dig down until you reach your goal.’ Go on, then, take it to the absolute end! However, most people try sitting in meditation just once, twice, maybe even five or ten times; but then they give up because they cannot make their minds peaceful. You have to keep at it until you experience peacefulness. If today’s meditation isn’t peaceful, try again tomorrow, and if tomorrow’s meditation is still not peaceful, then try again the following day. Continue like this until you achieve peace. There are some people who when they realize they are still not having much success in calming the mind will want to look for short cuts, methods that are easy and more suited to their character. But in truth the most universal of all meditation objects, suited to all people, already exist, namely, watching the breath and reciting ‘Buddho’.

I often like to compare developing concentration to someone digging for water. Since ancient times it has always been said that within the ground lies water. Now, suppose two men carrying picks and spades were to come into the forest, and each was to start digging a well. One man digs down to five metres and thinks in despair: ‘Could there really be water in ground as dry as this?’ He continues digging down to ten metres, but still doesn’t strike water. He thinks to himself: ‘Who in the village said there is water to be found? I don’t believe it!’ He then gives up and throws down his tools. When he returns to his village he declares that he no longer believes there is water in the ground, because he has just tried digging down to ten metres and found none. ‘The ground’s as dry as hell!’ he says, ‘how could there possibly be water there? Whoever said there was must surely be an idiot!’ The other man believes the people of old who said water lies in the ground. He digs down to ten metres but doesn’t strike water; nevertheless, he sticks at it no matter how arduous the digging is. He perseveres, and when he tires he takes a rest. He continues digging down to 15 metres and on to 20 metres, but still doesn’t hit water. ‘Never mind, just keep on digging’, he thinks to himself, ‘I’m not going to give up.’ He digs down to 30, 35 metres before finally striking a spring.